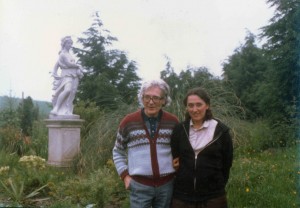

Symbiotic Earth: How Lynn Margulis rocked the boat and started a scientific revolution is a feature length documentary which presents a portrait of the great scientist and teacher Lynn Margulis who was at the helm of a significant paradigm shift in biology that affects how we look at ourselves, evolution, and planet Earth. Lynn Margulis traveled extensively, networking with collaborators in the sciences and humanities on ideas that stress the importance of symbiosis among all living things from bacteria to Gaia. Filmmaker John Feldman has interviewed many of these world famous scientists and thinkers. His film will bring to the general public these revolutionary ideas.Lynn Margulis, a courageous evolutionist and geoscientist, died unexpectedly of a stroke in November of 2011. A lively, personable, and down-to-earth scientist, her pioneering ideas cast doubt on accepted scientific “dogma” and challenged the establishment. She triumphed over ridicule, scorn, and chauvinism.

From the Frontlines

More than a biography of a great scientist, more than a look at the history and politics of science, and more than an explanation of current scientific theories, this documentary offers a coherent look at a contemporary paradigm shift that affects decisions we make on a daily basis about health, nutrition and the environment. The revolution it describes is as important and far-reaching as those of Copernicus and Darwin. This story needs to be told and disseminated widely.

Our “world views” incorporate the science we learned in school plus what we pick up from the media. But what happens when the science changes? This film addresses this challenge by telling stories from the frontlines of contemporary science that follow the development of new theories. It is designed so that a general audience can understand the science, “see” in a new way and “get-it.” Many of the ideas explored rely upon common sense notions that are already in popular culture and hark back to older, often ancient, ideas.

“This is a very important project because the science is moving very fast, and people deserve to be made aware of all the progress.” Dr. James Shapiro, Univ. of Chicago

Lynn Margulis inspired, worked with, and was inspired by colleagues from different disciplines, cultures, and generations. We visit universities and laboratories around the world, interview scientists who are thinking “outside the box” and learn about revolutionary and enlightening ideas. Archival footage, detailed and explanatory cinematography of the natural world (including the microbial world), animation, and original music enhance the drama.

Looking at forests instead of just trees. Traditionally, science has viewed living organisms as machines and in order to study them has used a reductionist approach which breaks things down into their component parts. Now scientists are also using an holistic approach – systems thinking – which is putting the world back together again, exposing properties that emerge from the system itself, and challenging our delusions that we can control and subjugate nature. “There is no Truth,” Margulis said, “but science is the best way of knowing.” She would remind us that after all these years of investigating, we still know very little about life.

Things work together more than they work apart. The evolution of life is as much – if not more – about joining and cooperation than it is about competition. Scientists are discarding the “selfish gene” idea. What does this mean for a society which has incorporated the metaphors “survival of the fittest” and “selfish genes” into its culture at many levels? Although we were all taught that random genetic mutations cause the variations on which natural selection acts, molecular biologist James Shapiro explains that this is not the case. Variation comes about because cells have the cognitive ability to actively change their own genome. In his words: What’s happened is we’ve gone from random mutations or accidents – which was the default assumption in the absence of any real knowledge of how these things work – to understanding that genetic change is an active process that cells carry out on their genomes. He also explains that hybridization is a major source of variation in plants and animals. Donald Williamson tells us that his hypothesis of larval transfer explains, among other things, that caterpillars and butterflies were once independent adult organisms that hybridized.

We are more than our genes. Much of our popular understanding of inheritance is based on the mid-twentieth century idea that our genes determine who we are, they were called “blueprints” or “the book of life.” Scientists are now finding that this gene-centered approach is far too simplistic. Instead of being a read-only memory system, our genes are a read-write system that is continually in touch with – and responding to – its environment. This idea is significant and relevant as we recall that the medical-industrial establishment is now offering “personal genetic profiles” as a way to predict future illnesses, yet the science behind these industries is increasingly being seen as overly simplistic, if not erroneous.

The microbial world. While many people still think of bacteria as “germs” and a plague on humanity, scientists now know that bacteria – our ancestors – are Earth’s primary producers and recyclers and that we couldn’t live without them. Indeed, it turns out that each of us is not the independent individual we think we are, but a community of organisms living together through complex symbiotic relationships. We contain more bacterial cells in our bodies than we do “human” cells. A better understanding of the role of bacteria in our bodies and in the environment is essential to understanding our health and the health of the environment.

The Environment is a Process. Next we look at the environment and the origins of the Gaia hypothesis. The environment is not a place, but a complex system of which we are a part. Once ridiculed, but now accepted as Earth Systems Science, James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis’s Gaia idea holds that collectively all of life regulates the temperature and chemical composition of the soil and atmosphere. Understanding this system is crucial as we come to grips with climate change and the growing demands our increasing population is putting on the soil, water, and atmosphere. Lynn Margulis often quoted Chief Seattle, “The Earth does not belong to us. We belong to the Earth.”